Dangerous Contraceptives

Quinacrine, Depo-Provera, Norplant & Women of Color Reproductive Justice

Dangerous contraceptions have been disproportionately promoted to women of color, indigenous women, women with disabilities, and women on federal assistance. Population control (largely through sterilization abuse), directed against people of color and indigenous people has an extensive history in the US and internationally. As many Third World countries began to resist the neo-colonial economic policies imposed by the World Bank and IMF, US government and business interests blamed the unrest on the Third World’s “overpopulation problem.”

Quinacrine: a dangerous form of chemical sterilization that can be administered during a pelvic examination…without your knowledge.

Q: What is Quinacrine?

A: Quinacrine is a form of chemical sterilization. It is inserted in the form of a pellet into the uterus, where it dissolves, scarring the fallopian tubes and possibly resulting in irreversible sterilization.

Q: Who distributes Quinacrine?

A: Quinacrine is manufactured and distributed by the North Carolina-based Center for Research on Population and Security, headed by Stephen Mumford and Elton Kessel. Mumford and Kessel peddle Quinacrine because they believe that immigrants, potential and actual, are a national security risk and that Quinacrine is the cheapest way to reduce their number. They express this view in the BBC film The Human Laboratory, now banned from global distribution by the Population Council.

Mumford and Kessel have distributed Quinacrine in countries around the world, including Bangladesh, Chile, China, Costa Rica, Croatia, Egypt, India, Indonesia, Pakistan, the Philippines, Venezuela, Vietnam, the United States, and possibly in Brazil, Guatemala, Thailand, Malaysia, and Romania. Worldwide, over 70,000 women have been sterilized with Quinacrine. Because Quinacrine can be administered during a simple pelvic examination, it is an ideal tool for sterilization abuse. In Vietnam, a hundred female rubber plant workers were given Quinacrine during routine pelvic examinations without their knowledge or consent.

Q. What are the side effects of Quinacrine?

A. The safety testing of Quinacrine has been extremely shoddy. In one Vietnam trial, participants who demonstrated serious side effects were simply dismissed from the study. Side effects that have been linked with Quinacrine include ectopic pregnancy, puncturing of the uterus during insertion, pelvic inflammatory disease, birth defects, cancer, and severe abdominal pains. Other possible effects include heart and liver damage and the escalation of pre-existing viral conditions. After conducting four in vitro trials, Family Health International determined that Quinacrine was too dangerous to continue testing. The World Health Organization has also recommended against further trials. No regulatory body currently supports Quinacrine.

For all its risks, Quinacrine may not even be effective. In many trials, women who received Quinacrine were also injected with Depo-Provera, a long-acting hormonal contraceptive. Given that Depo-Provera is also known to cause long-term sterility, it is difficult to ascertain how effective Quinacrine really is.

Q. If Quinacrine is not approved by the FDA for use as a form of sterilization, how can it still be given to women in the U.S.?

A: Quinacrine is an approved anti-malarial treatment. Since the FDA permits approved drugs to be used “off label” — that is, for uses other than the ones for which they were originally licensed — doctors can prescribe Quinacrine for whatever purposes they wish. Depo Provera, for example, was administered to women as a contraceptive long before it was approved for this purpose because it was already an approved form of cancer treatment. With private funding from such organizations as the Turner Foundation and Leland Fykes, Mumford and Kessel have been distributing Quinacrine for free to researchers, clinicians, and government health agencies worldwide.

The Children’s Hospital of Buffalo, New York has just approved the first quinacrine trial in the U.S. At least one doctor in Florida has publicly stated that he has begun distributing quinacrine off-label.

Q: What is to be done?

A: Women from your community may already be receiving Quinacrine without their knowledge. If you suspect that you or someone you know has received Quinacrine without consent, please contact the Quinacrine Alert Network, Committee on Women, Population, and the Environment.

What You Need to Know About Long-Acting Hormonal Contraceptives

Q. What is Norplant?

A. Norplant is a hormonal contraceptive for women. Norplant consists of six match stick-sized silicone capsules that are inserted into the upper arm, where they solely release small amounts of progestin. These capsules last for five years and must be inserted and removed by a medical professional.

Q. What are the pros and cons of Norplant?

A. PROS: Norplant is effective 24 hours after insertion and lasts for five years. The procedure is reversible if personnel trained in removal are available.

CONS: There are several adverse effects to using Norplant. The most common adverse effect of Norplant is the disruption of a woman’s menstrual cycle, resulting in prolonged bleeding, amenorrhea, or inconsistent spotting. However, Norplant is also associated with heart attacks, strokes, tumors, blindness, paralysis, coma, and depression. Norplant can also cause painful scarring where it is inserted. In addition, although Norplant is reversible if removed, addition, many women on Medicaid in the U.S. and women in the Third World have been refused removal or have been unable to find doctors who can remove it. If not removed after five years, Norplant increases a woman’s chance of ectopic pregnancy. Because of these side effects, over 50,000 women have filed suit against Wyeth-Ayerst, Norplant’s manufacturer.

Norplant does not protect against HIV or other sexually transmitted diseases.

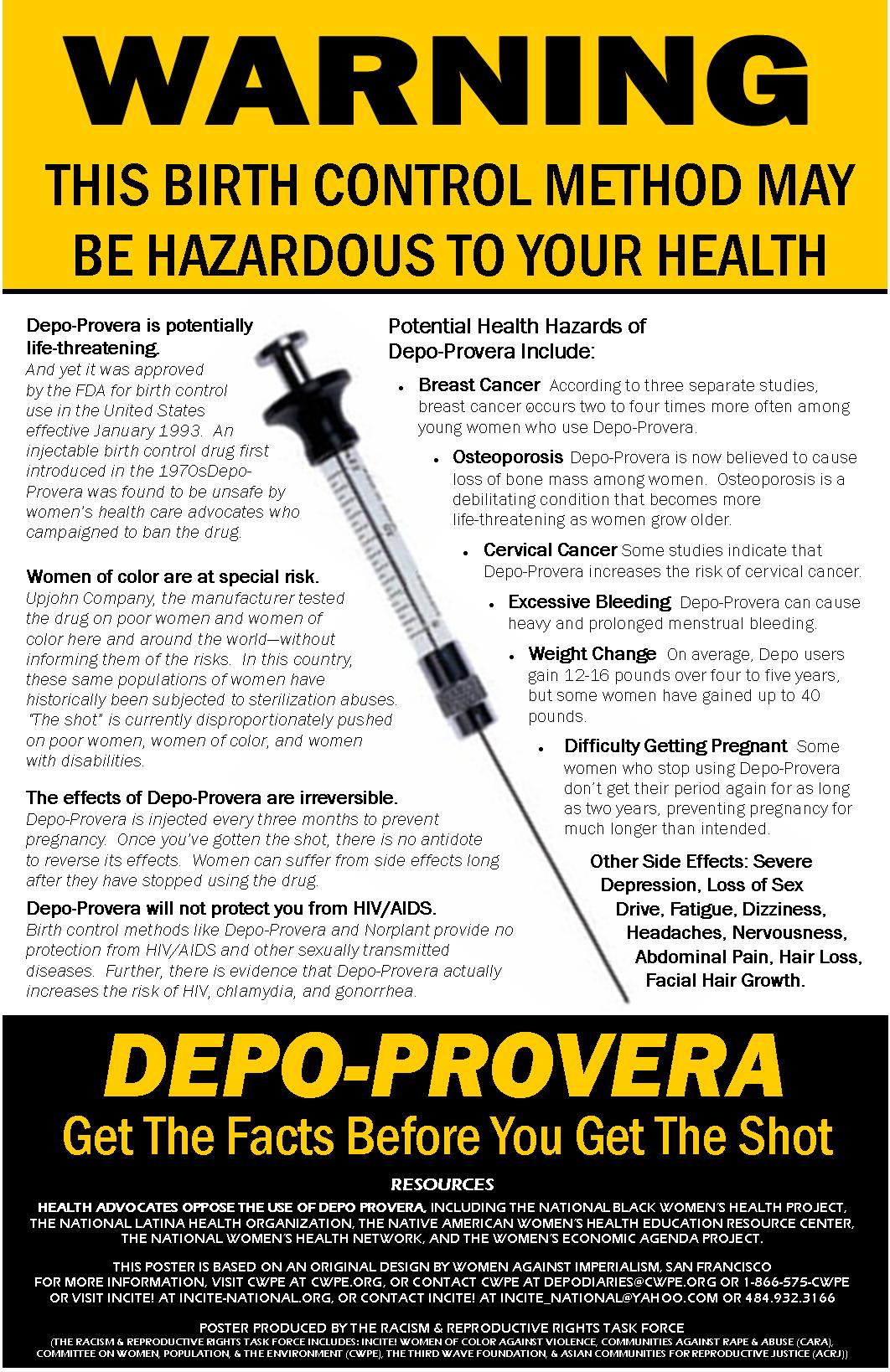

Q. What is Depo-Provera?

A. Depo-Provera is a hormonal contraceptive for women. It consists of the synthetic hormone progestin, which is injected into a woman’s bloodstream in large doses, causing suppressed ovulation, making the cervical mucus unable t o support sperm survival, and making the uterus unsuitable for egg implantation. Each administration prevents pregnancy for three to six months.

Q. What are the pros and cons of Depo-Provera?

A. PROS: A single shot of Depo-Provera is an effective contraceptive for three to six months, freeing a woman from continued responsibility for birth control methods.

CONS: Depo-Provera is associated with adverse effects such as menstrual disorders (irregular bleeding, amenorrhea, and heavy bleeding), skin disorders, tiredness, headaches, nausea, depression (often suicidal depression), hair loss, loss of libido, weight gain, and delayed return to fertility. In addition, to these short term effects, Depo-Provera is associated with long term effects such as breast cancer, osteoporosis, abdominal pain, infertility, and birth defects. It may also increase a woman’s risk of cervical cancer. Once injected, Depo-Provera cannot be removed or reversed, no matter how extreme the adverse side effects.

Depo-Provera does not protect against HIV or other sexually transmitted diseases. In fact, Depo-Provera may increase the risk of HIV transmission by altering the vaginal epithelium.

Q. Why are Norplant and Depo-Provera promoted, given their serious, adverse side effects?

A. Depo-Provera and Norplant have been disproportionately promoted to women of color, indigenous women, women with disabilities, and women on federal assistance. Population control, (largely through sterilization), directed against people of color and indigenous people has an extensive history in the US and internationally. As many Third World countries began to resist the neo-colonial economic policies imposed by the World Bank and IMF, US government and business interests blamed the unrest on the Third World’s “overpopulation problem.” In 1977, R. T. Ravenholt from the US Agency for International Development (AID), announced the plan to sterilize a quarter of the world’s women because, as he put it,

Population control is necessary to maintain “the normal operation of US Commercial interests around the world.” Without our trying to help these countries with their economic and social development, the world would rebel against the strong US commercial presence.

The state’s increased interest in limiting the growth of people of color in the US coincided with the expansion of post-World War II welfare provisions that have allowed many people of color to leave exploitative jobs. As a result, the growing unemployment rate among people of color means that non-white America is no longer simply a reservoir of cheap labor; it is considered “surplus” populations. Also, as land rights struggles increase between Native communities and the US government, it becomes in the interest of the US to have as few Native peoples as possible. One recently declassified federal document, National Security Study Memorandum 200, revealed that even in 1976 the U.S. government regarded the growth of non-white population as a threat national security.

With attitudes such as the one expressed above in place, coercive sterilization was regarded as acceptable, even respectable, until quite recently. In the 1970s, estimates run as high as 25 percent of Native women and one third of women in Puerto Rico receiving sterilizations without their informed consent. In 1979, it was discovered that seven out of ten US hospitals that performed voluntary sterilizations for Medicaid recipients violated the 1974 Department of Health, Education and Welfare guidelines by disregarded consent procedures and sterilizing women through “elective hysterectomies.”

Now that coercive sterilization is less acceptable, long-acting hormonal contraceptives like Norplant and Depo-Provera have become the primary tools against “overpopulation.” Several women’s organizations, such as the Black Women’s Health Project, the Native American Women’s Health Education Resource Center, the National Latina Health Organization, and the National Women’s Health Network, have opposed these methods as appropriate forms of contraception. Several state legislatures have considered bills which would give bonuses to women on pubic assistance for using Norplant. The Philadelphia Inquirer ran an editorial suggesting that Norplant might be a useful tool for “reducing the underclass.” Judges haven even required women convicted of child abuse or of drug use during a pregnancy to use Norplant. The Native American Women’s Health Education Resource Center has found that Indian Health Services (IHS), which routinely supposed Native women with Depo-Provera before it was even approved by the FDA for use as a contraception in 1992, still lacks adequate and uniform informed consent procedures for Norplant and Depo-Provera.

While sterilization abuse in the U.S. has ebbed somewhat since the 1970’s, population control efforts abroad have increased. Women in the Third World, moreover, are regarded as an expendable testing pool for contraceptive drugs. Before Norplant was introduced to the U.S., the device was tested on nearly half a million Indonesian women, most of whom received no counseling regarding the drug’s possible adverse effects. Many were not even told that the device had to be removed after five years to avoid the risk of ectopic pregnancy. In India, 3,5000 were given Norplant without screening to determine whether they were suitable candidates for the study. They received no warning of the drug’s possible adverse effects. The study was finally stopped due to concerns about “teratogenicity and carcinogenicity.” In both cases, women who wanted the implants removed had trouble finding doctors who were both willing and able to perform the procedure (Even in the U.S. many doctors know how to insert Norplant, but far fewer know how to remove it.).

Much of this information comes from Committee on Women, Population, and the Environment.